Previously in this ongoing series about my September 2012 holiday in Egypt, I recounted my impressions of the capital city of Cairo. (Seriously, if you haven’t read that one yet, you should do so immediately!) Now we proceed to Giza, the featured attraction of my sojourn in the Land of the Pharaohs. We’re still just getting started; there are many more Egyptian locales that I still need to get around to covering in this series!

Previously in this ongoing series about my September 2012 holiday in Egypt, I recounted my impressions of the capital city of Cairo. (Seriously, if you haven’t read that one yet, you should do so immediately!) Now we proceed to Giza, the featured attraction of my sojourn in the Land of the Pharaohs. We’re still just getting started; there are many more Egyptian locales that I still need to get around to covering in this series!

The pyramids at Giza have been tourist magnets since the days of the Roman empire, making them among the very first travel hotspots in world history. (International tourism originated during Roman times.) One of the joys of my own visit to the Giza Plateau was the knowledge that I was gazing upon the very same sights that had allured and mystified a hundred generations of travelers before me. While I took in countless spectacular things during my fortnight in Egypt, the ruins at Giza surpassed just about everything else. During the course of my stays in Cairo, I made three separate excursions to Giza; but I would eagerly go back yet again if the chance arose.

ON THE GIZA PLATEAU

Meet the pyramids

Three principal pyramids rise up from the stretch of desert known as the Giza Plateau, which is about 10 miles from Cairo’s city center. All were erected in the 26th century B.C.

• The largest and most celebrated is, of course, the Great Pyramid, which was built for King Khufu (also known to us as Cheops, the Hellenized version of his name). Originally soaring to a height of 481 feet, the Great Pyramid stood as the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years, until eclipsed by England’s Lincoln Cathedral in 1311 A.D. (Erosion has since reduced the height of the Great Pyramid to a still-impressive 455 feet.) The Great Pyramid has gained particular renown as the only one of the seven wonders of the ancient world that still survives intact in modern times.

• The second-biggest is the pyramid of Khufu’s son, Khafre (known alternatively by his Greek name of Chefren); at 448 feet it’s nearly as tall as the Great Pyramid itself. (Prior to erosion, Khafre’s pyramid topped out at 471 feet.)

• The bronze for third-largest goes to the pyramid of Khafre’s son, Menkaure (a pharaoh who also goes by the Hellenized name of Mykerinos); its height is 204 feet, down from 215 feet before the ravaging effects of erosion did their thing.

In addition to the main pyramidal trinity, the site contains several much smaller buildings in that shape, known as “Queen’s Pyramids” (in reference to the personages who were buried in them); and a variety of other, more conventional tombs. (The three largest pyramids were, themselves, conceived as mausoleums for the kings who decreed their construction. The mummies of those kings have never been found; their remains may have been purloined by grave-robbers in the distant past. Whether those grave-robbers succumbed to the curse of the mummy is anyone’s guess.)

The world’s first skyline. Left to right: the Great Pyramid; the pyramid of Khafre; and the pyramid of Menkaure. One of the Queen’s Pyramids is visible at the extreme right.

The pyramids are remarkable works of engineering that surely deserve to be considered among the world’s first great works of architecture. As with Stonehenge and the moai of Easter Island, we’re not completely sure how they were built, in light of the primitive technology available to the society that designed them. It’s no wonder that, when writing a midterm examination in a freshman year history course at university, I speculated that benevolent space aliens assisted the ancient Egyptians in the construction of their iconic monuments. (I received an “F” on that exam, but it’s not my fault that my professor wasn’t open to my revisionist scholarship.) 🙂

My experience visiting Giza’s pyramids wasn’t limited to admiring them from the outside. Did you know that you can go inside them too? My tour company procured tickets entitling members of my group to enter Menkaure’s pyramid. That one, as mentioned, is the smallest of the main trio of pyramids at Giza; but I was still quite excited. How often are you given the opportunity to step into a 4,500-year-old building? (Only 100 tickets a day are released for entry into the Great Pyramid, most of which end up with scalpers and such. Needless to say, I didn’t score any. I’m not sure about the comparative difficulty of obtaining passes for the pyramid of Khafre.)

So what was it like inside, after reaching the bottom of the steeply sloping ramp? Well, it was oppressively hot, as you’d expect in an unventilated chamber on a day when outdoor temperatures approached 100 degrees Fahrenheit; and there was nothing to see but a bunch of empty rooms. (The original contents of the pyramids have long since been removed, by plunderers through the ages and then by archaeologists.) But I didn’t feel any letdown; what was important was that I could now say that I’d walked inside an Egyptian pyramid! Vacation activities don’t get any more bucket list-y than that.

The Great Sphinx: riddling travelers for four and a half millennia

Just north of the pyramids on the Giza Plateau sits (or, more accurately, crouches) the equally venerable Great Sphinx. In mythology, a sphinx is a hybrid creature fusing the body of a lion with the head of a human or a cat. However, depictions of sphinxes in ancient Egypt invariably bore human heads. (Sphinxes also appeared in the ancient traditions of Greece, Mesopotamia, and India.) Like many other mythological characters, sphinxes were often depicted in sculptures. Of the multitude of such statues crafted in antiquity, the Great Sphinx at Giza is almost certainly the largest; it measures 241 feet in length and 66 feet in height.

Like the pyramids, the Great Sphinx is shrouded in enigma; in fact, we don’t even known what its creators called it. (The English word “Sphinx” comes from the Greek language. Fun fact: our word “sphincter” derives from the same Greek root. This makes sense when you realize that “sphinx” is Greek for “strangler.”) Some people believe that the Great Sphinx considerably predates the pyramids, and that it’s a remnant of an even older civilisation that vanished without a trace (kind of a Middle Eastern analogue to the lost continent of Atlantis). There’s no credible evidence to support that theory, but it’s cool to think about.

The Great Sphinx’s aura of mystery is enhanced when it’s viewed after dark. One of my three outings to Giza was an evening excursion for a sound-and-light show. During that show, the pyramids and sphinx are lit up in ever-changing colours. The Great Sphinx in particular looks hauntingly beautiful when illuminated at night:

The Great Sphinx and the Pyramid of Khafre, colourfully illuminated during the sound-and-light show.

I’ve been told that the content of the show, featuring narration by Omar Sharif, was quite good; but I’m not in a position to confirm those reports. So intently was I focused on my picture-taking that I didn’t hear most of the audio.

Come sail away . . . to the afterlife

You probably wouldn’t expect to come across a boat in the desert. Found buried at the base of the Great Pyramid was the “Khufu ship,” a wooden ship that was built circa 2500 B.C. It’s impressively large, measuring 143 feet in length.

This vessel has also been dubbed a “solar boat” (or “solar barque”) because it was buried for the purpose of enabling the deceased Khufu to sail through the heavens with the sun god, Ra. It was interred in 1,224 separate pieces, presumably because the ancient Egyptians lacked the necessary equipment to lower such a massive object into a pit. After being dug up by archaeologists in 1954, those components were painstakingly reassembled without the benefit of IKEA-type instructions. Since 1982, the reconstructed ship has been on display in a museum beside the Great Pyramid. A second solar boat, also belonging to Khufu, was discovered in 1987 in a pit adjacent to the one from which the first Khufu ship had been removed; the excavation of Khufu’s second ship was completed in February 2012. It’s in the process of being restored, and will then go on display to the public. Khufu ship no. 2 is believed to be somewhat smaller than its sister ship, although its exact size won’t be known until the reassembly is complete.

A number of other solar boats, also dating back to the Bronze Age, have been unearthed at royal necropolises throughout Egypt. One of them, found in Abydos, is believed to be over 400 years older than the Khufu ships.

The ancient Egyptians weren’t known as a great seafaring people; maybe that’s because all their best ships were built for dead guys.

Camel rides around the pyramids (I was too cowardly to take one, but I can still write about them)

In the public mind, camels are indelibly associated with caravans in the Sahara Desert. Surprisingly, those majestic humped mammals aren’t actually native to the African continent. They first arrived in Egypt when Persian conquerors brought them circa 525 B.C. Today, it’s difficult to imagine Egypt without them. Camels are especially ubiquitous in the vicinity of the pyramids.

A popular pastime at the Giza Plateau is to circumnavigate the pyramids on a camel, thereby beholding the timeless monuments from a unique vantage point. Here you can see two members of my tour group, Toos and Sharon, about to embark on such a ride:

It’s fair to say that a camel ride is to Giza as a gondola ride is to Venice: clichéd and expensive, but obligatory. Nevertheless, during both of my daytime visits to Giza, I declined the chance to take such a jaunt myself. The reason: I was afraid. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m acrophobic; and a passenger on a camel has to sit pretty high up off the ground. Additionally, I didn’t need to pose on a camel in order to obtain a coveted profile photo for my Facebook page; I already had a photo of me sitting on a camel, taken in Marrakech, Morrocco in February, 2011.

Me sitting on a camel in Marrakech in February 2011. If you want to believe that I actually went for a ride on that thing, I won’t stop you.

Notice that I said “sitting on a camel,” not riding on one. That creature in Marrakech remained stationary the whole time. As soon as the photo opportunity that yielded the above shot had concluded, I was like, “Let me off this thing!” By the way, note also that at least the seating areas on the Moroccan camels were equipped with large hoops to hold onto, which helped reduce my fear of falling off. In contrast, the camels at Giza offered only a tiny knob in front of the saddle to grab. That set-up just didn’t inspire confidence — particularly given that camels are prone to wobbling as they walk. And lest you think my fears of falling off a camel were exaggerated, it’s something that’s been known to happen to other tourists. So there! 🙂

Beware the ali babas!

In my article about Cairo, I talked about the “ali babas” — Egyptian merchants who practice deceptive techniques upon their customers. Those scoundrels aren’t only found in gift shops. They also abound at tourist attractions like the Giza Plateau — basically, anywhere that they can expect to find a large supply of naive and trusting visitors. Around the pyramids, these scam artists are constantly in your face, pressuring you to let them show you around or assist you in taking pictures — with the expectation that you’ll compensate them for such unsolicited and unnecessary services. Often, the ali babas at Giza will claim to work for the government — a claim that’s always false.

Ali babas can be shameless, as the following anecdote illustrates. During my first visit to Giza I was accompanied by Mohamed, a driver/guide whom I’d hired through the concierge desk at my Cairo hotel. (This was at the beginning of my trip when I hadn’t yet joined up with my tour group and I was exploring on my own.) It was Mohamed who instructed me in the ways of the ali babas, and he repeatedly interceded when they were harassing me. At one point I wandered off to take some photos. Taking advantage of my temporary separation from my protector, a young man approached Mohamed and asked for permission to steal me away as a client. As an incentive, the would-be usurper offered to share with Mohammed 50% of the fee to be received from me. That’s right, this ali baba tried to poach me from my own guide! Fortunately, Mohamed is an honourable man and resisted these overtures.

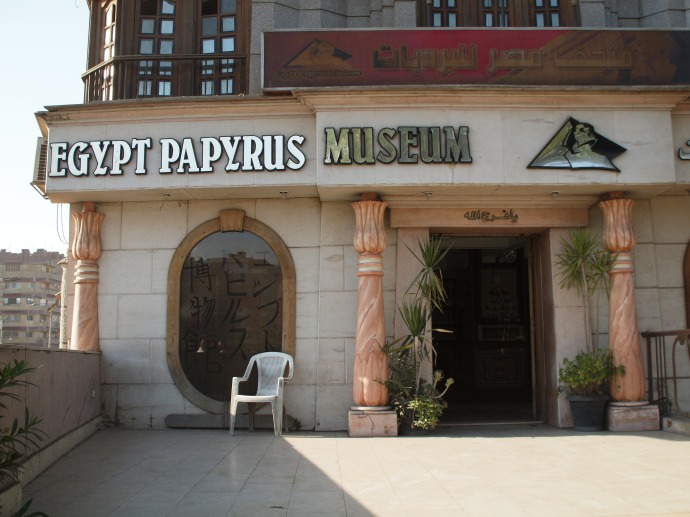

THE PAPYRUS “MUSEUM”

After Mohamed and I checked out the pyramids and sphinx, we made one additional stop in Giza: the Egypt Papyrus Museum. It’s one of many facilities of its type that I noticed throughout the country, all of which purport to be “museums.” The one with my favourite name bore the delightfully rhyming moniker of “Osiris Papyrus.” 🙂 (Osiris was the Egyptian god of the underworld and the afterlife.)

Here you can see me hanging with Mohamed inside:

Papyrus, a precursor to paper that was used by the ancient Egyptians, is a writing surface made from the papyrus plant (a type of sedge). Inside a papyrus museum, you’re treated to a free demonstration of the process by which papyrus is made — a technique that’s remarkably similar to the way it was done in the age of the Pharaohs. You’re then invited to linger in the “museum,” whose walls are lined with artistic prints on papyrus that are available for purchase. The quality of the prints tends to be quite good; just realize that the place is really a glorified gift shop. Unlike in most museums, there are no exhibits to see, and no collection of artifacts for you to contemplate. The demo of the making of papyrus was interesting, though. Have a look at some highlights:

I suspect that the Egypt Papyrus Museum was among the retail establishments in that part of the world that pay kickbacks to guides who bring in customers. However, I have no idea whether Mohamed stood to receive any compensation for referring me. In any event, I made no purchases there.

PARTING THOUGHTS

The title of this blog post was inspired by the excellent Werner Herzog documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which I saw last year. That movie, a rare docu that’s presented in 3-D, is about a cave in Chauvet, France whose walls contain paintings etched over 30,000 years ago. The amount of time that separates us from the artists who created those paintings forms an unbridgeable gulf. At one point in his narration, Herzog poses the question as to whether, when we attempt to understand the paleolithic cave painters of Chauvet, we “look back into an abyss of time.”

The pyramids and Great Sphinx, of course, are much more recent creations; but still I found it difficult to wrap my mind around the sheer quantity of time that’s elapsed since they were brought into being. Even 4,500 years is an unfathomably long stretch. When the Roman empire held sway, the monuments at Giza were already older than the Roman ruins such as the Forum are in the 21st century.

Someday our own lives will have receded 4,500 years into the past; our hopes and dreams will have long since been forgotten. Paradoxically, to gaze upon the pyramids and the Great Sphinx is to be reminded of of our own impermanence, even as they themselves have endured through the ages.

Mark Twain visited Giza in 1867. Although he’s best known as a humorist and novelist, the dude was also an amazing travel writer. In his travel memoir Innocents Abroad, he shared his own thoughts regarding the dizzyingly long interval through which Giza’s monuments have carried on. In that vein, particularly striking for Twain was the Great Sphinx, whose terrifying visage seemed to reflect back all that it had witnessed during its journey “over the ocean of Time”:

“The great face was so sad, so earnest, so longing, so patient. There was a dignity not of earth in its mien, and in its countenance a benignity such as never any thing human wore. It was stone, but it seemed sentient. If ever image of stone thought, it was thinking. It was looking toward the verge of the landscape, yet looking at nothing — nothing but distance and vacancy. It was looking over and beyond every thing of the present, and far into the past. It was gazing out over the ocean of Time — over lines of century-waves which, further and further receding, closed nearer and nearer together, and blended at last into one unbroken tide, away toward the horizon of remote antiquity. It was thinking of the wars of departed ages; of the empires it had seen created and destroyed; of the nations whose birth it had witnessed, whose progress it had watched, whose annihilation it had noted; of the joy and sorrow, the life and death, the grandeur and decay, of five thousand slow revolving years. It was the type of an attribute of man — of a faculty of his heart and brain. It was MEMORY — RETROSPECTION — wrought into visible, tangible form. All who know what pathos there is in memories of days that are accomplished and faces that have vanished — albeit only a trifling score of years gone by — will have some appreciation of the pathos that dwells in these grave eyes that look so steadfastly back upon the things they knew before History was born — before Tradition had being — things that were, and forms that moved, in a vague era which even Poetry and Romance scarce know of — and passed one by one away and left the stony dreamer solitary in the midst of a strange new age, and uncomprehended scenes.

The Sphynx is grand in its loneliness; it is imposing in its magnitude; it is impressive in the mystery that hangs over its story. And there is that in the overshadowing majesty of this eternal figure of stone, with its accusing memory of the deeds of all ages, which reveals to one something of what he shall feel when he shall stand at last in the awful presence of God.”

(Innocents Abroad, Chapter LVIII)

Twain’s lyrical prose can be paraphrased as: “The Great Sphinx is really old.” 🙂 His words do convey the idea, also expressed in Herzog’s film, of how the products of mankind’s creative impulses can long outlive the societies in which they arose — to a point where all memory of the people who first imagined them has been obliterated. As the noted philosopher Cat Stevens has observed, “You’re only dancing on this Earth for a short while.” But the pyramids and the Great Sphinx dance on and on. For us as for Twain, to stand in their presence is to look back into the abyss of time.

Read the other parts of my continuing series on Egypt!

Prologue: Singing karaoke in Egypt

Part 1: Cairo

Part 3: The Valley of the Kings

Part 4: Saqqara and Memphis

Click here to follow me on Twitter! And click here to follow me on Instagram!

Very entertaining Harvey. Like your description of the Ali babas….

LikeLike

@Shane: Thank you! There are more ali baba stories coming as the series continues! And I thought it was ironic that the the awesome guide who protected me from the ali babas in Giza had the same name as the guy who ripped me off in Cairo (although maybe it’s not so surprising, given the distribution of names in Egypt). 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderfully put Harvey!

LikeLike

@Toos: Thank you for the compliment!

LikeLike

Wonderful photos! The pyramids do look spectacular and I hope to finally make it over to Egypt. This post reminds me of time I spent in North Africa, amazing moments.

I really liked seeing how papyrus is made. Great idea to include the pictures.

LikeLike

@Pola: Thanks! You should totally go to Egypt! The pyramids and sphinx were definitely spectacular, and of course there’s so much else to see in Egypt as well.

LikeLike

Wow, impressive shots here Harvey! I haven’t been to Egypt yet….I think I need to add camel-riding to my to-do list though, haha!

LikeLike

@Red: Thank you. You should definitely go to Egypt. And since you’ve done things like walking above the treetops in Borneo, I have no doubt that you’d be brave enough to ride a camel around the pyramids. 🙂

LikeLike

Visiting the Pyramids at Giza is still to this day one of my favorite travel experiences. We rode the camels and visited the papyrus museum, too. I bought a beautiful papyrus painting with Queen Nefertiti on it. What a great experience for you to have and such a unique place to sing karaoke!

LikeLike

@Ellen: It’s great that you and Justin were able to have that experience too — and that you weren’t too scared to ride the camels there. 🙂

Some of those papyrus prints were pretty amazing; I just wish those shops didn’t pretend to be something they’re not (i.e., a museum). 🙂

Egypt was only one of many spectacular places where I’ve sung karaoke. The World Karaoke Tour definitely adds another dimension to my travels.

LikeLike

Enjoyed the story and photos. Can’t wait for my trip to Egypt! Every year I postpone it… waiting for the end of political crisis (safety concerns).

LikeLike

@memographer: Stop postponing it! The safety concerns for tourists there are minimal, and don’t justify depriving yourself of the experience of seeing these sights in person! And I’m glad you enjoyed this article.

LikeLike